Note: This article uses certain terms directly from historical sources or archives that might be considered outdated today but are included to accurately reflect the language of the time.

In the mid-20th century, a shadow war was waged against LGBTQIA+ Americans under the guise of patriotism and morality. While the Red Scare of the Cold War hunted for alleged communists, a parallel “Lavender Scare” purged thousands of Gay, Lesbian, and Gender-nonconforming people from government service. This was a state-sanctioned campaign of cissexism (also known as transphobia) and heterosexism (also known as homophobia and biphobia etc): a deeply political and profoundly oppressive strategy that cast the LGBTQIA+ communities as threats to the nation. However, it would be a dangerous mistake to view this history as distant or isolated. Today, across the United States and beyond, we see a renewed resurgence of these same logics under different guises: bills criminalising Trans existence, denial of Trans healthcare, moral panics about Drag queens reading books in schools, and extreme technological surveillance of LGBTQIA+ lives are contemporary manifestations of the Lavender Scare. Understanding this historical continuity is essential because the mechanisms of demonisation and pathologisation enacted during the Lavender Scare continue to shape LGBTQIA+ experiences today, both socially and in workplaces.

This article explores the Lavender Scare’s historical context under Cold War McCarthyism (including Executive Order 10450), the broader demonisation and pathologisation of LGBTQIA+ communities, and how these logics connect to other forms of oppression at the time. It also examines how the narratives that drove the Lavender Scare persist in our present-day workplaces. Crucially, we’ll see that cissexism and heteorsexism in organisations aren’t about a few “bad apples” – they are structural realities. Finally, we issue a call to action for leaders to confront these oppressive systems within their own spaces.

The Lavender Scare: A Cold War ‘Witch Hunt’

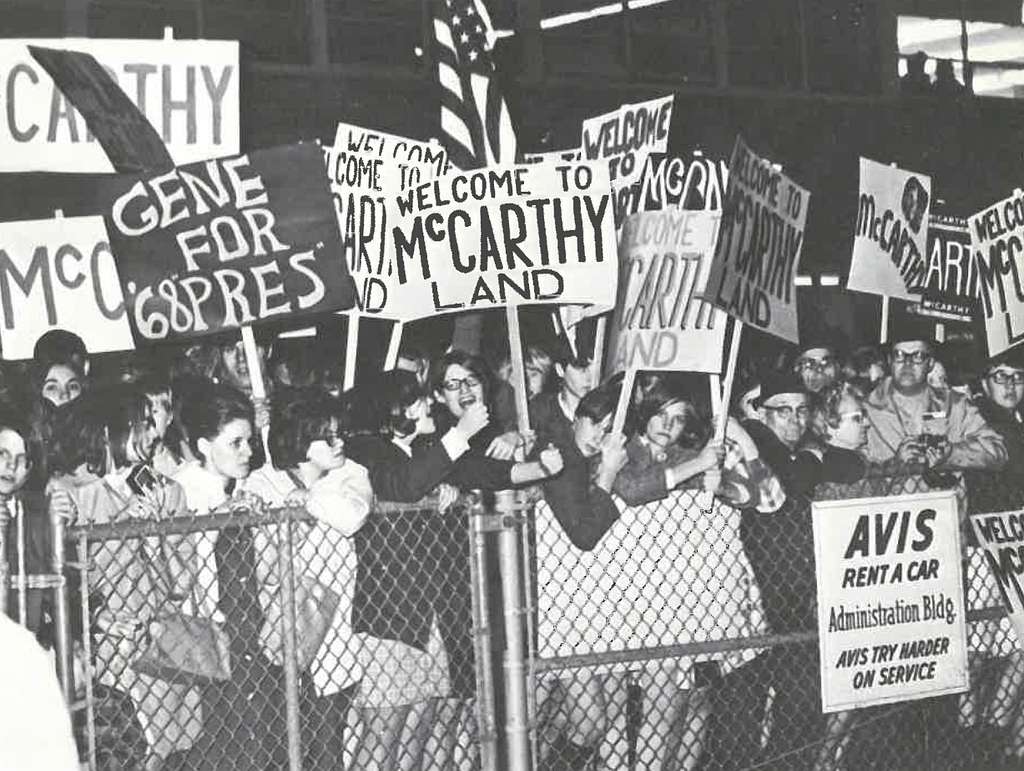

In 1950, as Cold War paranoia raged, U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy infamously claimed to have a list of 205 communists working in the State Department. When his Red Scare crusade failed to uncover the imagined communist cabal, McCarthy shifted his focus to a “more vulnerable” target: Gay people. He and others cynically conflated homosexuality with treason, declaring that Gay Men and Lesbians posed a security risk to the United States. The twisted logic was that LGB+ people because of the projected shame and stigma of their identities could be blackmailed by foreign agents – and thus were rendered “Un-American” by default. As McCarthy put it, the great struggle between America and communism was not just political but moral, lumping atheism, adultery, premarital sex, and homosexuality together as internal threats to so called ‘American values’. In the fabricated panic that followed, mere suspicion of being Gay or Trans could destroy careers and lives.

What came to be known as the Lavender Scare unfolded as a widescale witch hunt (histories that deserve their own analysis!). In 1953, President Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450, which officially barred “sexual perversion” – a thinly veiled reference to homosexuality – from the federal workforce. This order mandated intrusive investigations into employees’ private lives and led to thousands of firings. By conservative estimates, 7,000–10,000 federal workers (civil servants, soldiers, contractors) lost their jobs due to their real or perceived sexuality during the Lavender Scare. Many were interrogated, outed, and publicly shamed; some were driven to suicide. Eisenhower defended the purge by saying government service was a “privilege” that could be denied to those who fell short of the era’s ‘moral standards’. In reality, LGBTQIA+ employees who had done nothing inherently ‘disloyal’ became scapegoats for a state deploying heightened militarisation and policing to control and exclude communities it positioned as threats. While the Red Scare largely failed to uncover actual communists, the Lavender Scare “victimized Americans in their workplace and beyond for the latter part of the 20th century”. It was a reminder that notions of “loyalty” and “morality” were wielded as weapons to enforce Heterosexual and Cisgender conformity.

Pathologised, Criminalised, Deemed ‘Un-American’

How did officials justify this blatant persecution? They wrapped heterosexism and cissexism in the language of medicine, law, and patriotism – powerful narratives of social control. In 1950, a Senate investigative report titled “Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government” concluded that Gay people were unsuitable as federal employees because Homosexuality was a ‘mental illness’. The report flatly stated that Homosexuals “constitute security risks” since those who engage in “overt acts of perversion lack the emotional stability of normal persons”. By defining LGBTQIA+ communities as sick, the government cast their exclusion as a matter of public safety and even of their safety. This pathologisation was soon formalised by psychiatry – in 1952 the American Psychiatric Association’s first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual listed homosexuality as a “sociopathic personality disturbance”. Being Gay or Lesbian was framed as an ailment to be cured or contained, not an identity like any other way to be human. Trans identities were likewise treated as cureable; for decades, medical institutions labeled being Trans as “gender identity disorder,” a diagnosis only very recently reformed. The effect of this pseudo-scientific stigma was to legitimize anti-LGBTQIA+ bigotry as if it were rational and even kind – “for their own good.” It was nothing of the sort: it was oppression in a white coat.

Hand in hand with pathologisation was criminalisation. During the Lavender Scare era, simply existing as LGBTQIA+was criminalized in many contexts. Consensual intimacy between two people of the same Gender/Sex was outlawed in states across the country, and police forces zealously enforced these laws. Gay bars and gathering spots were raided; Men and Women were arrested and charged as “sex perverts” for consensual acts of love and/or pleasure. Likewise, many cities had so-called “masquerade laws” that made it illegal to wear clothing not associated with one’s birth-assigned Sex – in effect, a ban on Gender expression. Through the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, police utilised these laws to harass and punish LGBTQIA+ people for how they dressed or presented their Gender. A Trans Woman wearing a dress, or a Gay (or not-Gay!) Man wearing makeup could be handcuffed and booked for “cross-dressing.” By branding LGBTQIA+ people as deviants, the state reinforced the notion that they presented a danger and needed to be criminalised accordingly. This dovetailed with the constructed narrative of being “Un-American.” The Lavender Scare thrived on portraying LGBTQIA+ individuals as alien to the nation’s core values – as threats to the idealised American family and the sanctity of the (Heterosexual) ‘American way of life’. Officials and media of the time routinely described LGBTQIA+ folks as moral degenerates, subversives, and traitors in waiting. In public discourse, patriotism was equated with Heterosexuality and Cisgender conformity. Those who fell outside those lines were painted as internal enemies in a Cold War for “American values.” The irony is bitter: in the name of fighting an “un-American” threat, the government carried out policies that trampled the very freedoms and liberties America professed to uphold. A common tale.

Scapegoating Across Communities: Interlocking Oppressions

Just a few years earlier, was the internment of Japanese American people during World War II. While it predated the Lavender Scare, it stemmed from the same poisonous root: the presumption that entire communities can be collectively punished as threats. In 1942, President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 authorised the round-up of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Ultimately, around 120,000 people of Japanese descent – including 70,000 U.S. citizens – were forcibly removed and incarcerated in internment camps simply because of their ethnic origin (Incarceration of Japanese Americans – Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)). No charges, no trials, just racism encoded in policy. Families lost their homes, businesses, and years of their lives behind barbed wire because of their ancestry. This atrocity was an obvious parallel to later purges: whether the bogeyman was “the Japanese spy” or “the communist sympathiser” or “the sexual deviant,” the state used national security as a pretext to persecute folks they had manufactured into a threat. People of Colour, marginalised ethnic groups, LGBTQIA+ people, those with left politics – all were, at one time or another, branded “enemies within.”

In the late 1940s, prior to McCarthy’s list, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was already spotlighting Hollywood, ostensibly to root out communists in the film industry. In truth, this crusade was deeply antisemitic. One commentator noted that for HUAC, “for ‘communist’, read ‘Jew’”. Antisemitic rhetoric at the time frequently positioned Jewish people as a “fifth column,” a term originating during the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s. It described a supposed internal group secretly supporting external enemies by plotting sabotage and betrayal from within. Antisemites adapted this language to falsely portray Jewish communities as inherently disloyal, untrustworthy, and aligned with global communism. Indeed, a disproportionate number of those blacklisted in Hollywood were Jewish, and certain Congress people made barely-veiled antisemitic attacks by reading out lists of Jewish names as supposed proof of a Red conspiracy. This conflation of Jewish identity with communism was not isolated; rather, it was rampant globally at the time. For instance, as the Brazilian Communist movement peaked in the mid-1930s, politicians and intellectuals there similarly emphasized presumed ties between Jews and communism. The Brazilian foreign ministry responded by designing increasingly restrictive immigration policies, and by 1937, stringent rules explicitly barred all Jews, including tourists and business visitors, from entering Brazil (UC Press). Thus, the same frenzy that painted Japanese Americans as inherent traitors, cast Jewish Americans as disloyal subversives. Both groups served as convenient scapegoats for political elites intent on maintaining control by manufacturing social anxieties and generating paranoia.

Black Americans also experienced anti-Communist repression entwined with racism. The Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum in the 1950s, demanding an end to Jim Crow and racist terror. In response, segregationists and the federal government alike frequently tried to discredit Black activists by tarring them as communists. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., for instance, was relentlessly surveilled by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who obsessively tried to link King to communism in order to undermine his moral authority. Hoover’s FBI launched COINTELPRO, a counterintelligence program, which framed civil rights leaders as pawns of a Soviet plot. A 1963 FBI memo even declared King “the most dangerous Negro” in America and set out to “mark him…as the most dangerous” leader, explicitly trying to demonize King and criminalise Black protest (“The Most Dangerous Negro” | Jacob Silverman | 2018-2019 | University Writing Program | Brandeis University). The bureau’s logic held that civil rights activism was “un-American” and thus fair game for violent suppression. In truth, anti-communism was a cover for maintaining White Supremacy. Black freedom fighters from Paul Robeson to Rosa Parks were smeared as Reds to marginalise their demands for justice. Robeson – a world-renowned Black singer, actor, and activist – had his passport revoked in 1950 because his outspoken advocacy for racial equality and labor rights (and his friendly stance toward the USSR’s anti-fascism) made him a “prime target of militant anticommunists” (The Many Faces of Paul Robeson | National Archives). The U.S. government literally imprisoned Robeson within its borders for much of the 1950s, silencing his voice internationally in the name of fighting communism. Here was Racism and anti-Communism fused: a Black Man who challenged the power structure was labeled a traitor and neutralised.

In all these examples, ‘loyalty to the state’ became a demand and requirement to suppress dissent and critique. But when some people’s lives are subject to greater proximity to death because of the very state demanding loyalty, loyalty is something no one should have to give.

Intersectionality, the term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, teaches us that these systems of oppression are interconnected. During the Lavender Scare, one could stand at the intersection of multiple targeted identities – for example, an LGBTQIA+ person of Colour or a Jewish Gay Man – and face compounded oppressions. Consider the Black Queer activist Bayard Rustin: he was a chief architect of King’s 1963 March on Washington, yet was often relegated to the shadows because his identity made the Civil Rights Movement vulnerable to attack. Rustin had been arrested in the 1950s on a “morals charge” (targeting his Homosexuality), and White Supremacists eagerly weaponised that fact to try to discredit the movement’s leadership. His experience showed how homophobia was used to reinforce racism: White Supremacists seized on anti-Gay ideas to weaken the push for racial equality. The oppressions of that era bolstered each other. Misogyny was in the mix too – Women who defied Gender norms or authority (from Hollywood actresses branded “Red” for being too outspoken, to Lesbians who dared to live independently) also faced suspicion and sanction. The common thread was a society stratified by power: those who deviated from the White, Male, Heterosexual, Cis, Christian ideal were treated as expendable problems to be disposed of or erased. The Lavender Scare thus stands alongside Japanese internment, antisemitism towards Jewish folks and the FBI’s war on Black activists as part of a broader machinery of demonisation. Different excuses, different targets – but ultimately, all with the purpose of shoring up and concentrating power in the hands of a few.

Today, if we understand the laws and policies historically weaponised against LGBTQIA+ communities, we could certainly challenge them on that basis. However, our actions would be far more powerful and transformative, if we intentionally built coalitions across marginalised groups to disrupt the intersectional inequities embedded across these oppressive structures. By adopting what we coin in our White Paper as an ‘Issue-led approach’ to change-making, we collectively address the roots of oppression, ensuring lasting solutions that uplift and relieve all marginalised communities simultaneously.

Criminalisation as a Construct (and Tool of Oppression)

It is vital to understand that the criminalisation we’ve been discussing, whether of LGBTQIA+ people, racialised communities, or marginalised Genders, is socially constructed and mutable. “Criminal” is not an inherent quality that certain people or acts possess; it is a label created (and removed) by society through law and custom (Policing our Imaginations: The Role of the Police in Engendering Gender Violence – Fearless Futures Limited). Who gets labeled a criminal, and what actions are deemed crimes, has always reflected the values and needs of those with power, rather than an objective measure of harm or ‘evil’. As Hanna Naima McCloskey, Founder and CEO of Fearless Futures, aptly puts it:

“Let’s think of it a different way: why do the police patrol the streets, rather than the offices of investment banks whose actions produced the subprime mortgage crisis that cast millions of people into (further) poverty, or whose lending decisions fund climate catastrophe?”

This selective criminalisation serves to protect elite interests rather than public, collective wellbeing. The British colonial authorities criminalised Homosexuality across their empire, not because of local clamour for it, but to impose Victorian social control. Laws against ‘cross-dressing’ (itself a ludicrous notion in suggesting items of clothing inherently belong to one Gender), for example, were purely patriarchal inventions. If Women defied expectations by wearing trousers, they might next demand the rights of Men who commonly wear trousers, or Men’s economic independence, or freedom from Men’s authority. Thus, by criminalising Women who adopted so called masculine attire or roles, society sought to preemptively contain any challenge to Men’s dominance. Such laws were never about clothing; they represented attempts to control Women’s bodies, choices, and agency.

Why does this matter? Because recognising the socially constructed nature of criminalisation shifts our perspective: it forces us to ask “who decided this was a crime, and why?” We often find that the answer is those with power, in service of keeping that power.

Understanding this is liberating. It means that injustices enshrined in policy or practice are not fixed, they can be removed. But it also serves as a warning: if we do not stay vigilant, those in power can redefine what is criminal to suit new ends. The process of demonisation is ongoing and can be redirected at new targets (for instance, consider how after 9/11 in the 2000s, Muslim and South West Asian communities suddenly faced intense surveillance and suspicion, a new chapter of “un-American” othering). Social constructs can be rebuilt for better or worse. So we must actively challenge the false constructs – like the idea that LGBTQIA+ people are in any way prone to misconduct by virtue of their identity – and replace them with frameworks of equity and reality. As we at Fearless Futures love to remind people of: “Crime” (and by extension, any claim that X group is criminal or dangerous) must be interrogated as a function of power, not accepted compliantly. The Lavender Scare’s legacy demands that we never again allow law, medicine, or patriotism to be twisted into instruments of oppression.

Echoes in Today’s Workplaces

It might be comforting to view the Lavender Scare as a bygone horror, a peculiar product of a more bigoted time. Trans people in the United States are currently experiencing a new iteration of the Lavender Scare. Over the last decade (and ramped up in recent months after Trump 2.0) hundreds of bills targeting Trans existence have been introduced at both state and federal levels. These bills seek to strip away access to healthcare and legal legitimacy as well as suppress education and public dialogue about Gender identity. This is not a series of disconnected legislative attempts. It is a structural project of erasure.

Documented by Trans journalist Erin Reed, this legislative infrastructure now includes over 800 anti-Trans bills. And in 2025, under a newly elected federal administration, this attack reached the executive level. Executive Order 14168, titled Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government, mandates that all government-issued documentation reflect “biological sex” only. Section 3D compels agencies such as the State Department and Office of Personnel Management to eliminate Gender identity from records entirely.

This is not symbolic. It is administrative violence. By removing recognition of Trans people from federal documentation, this order enacts an ontological denial. It declares through policy that Trans people do not, and cannot, exist within the architecture of the state. It is justified under a false claim to scientific objectivity, mirroring the 1950s classification of Homosexuality as a “sociopathic personality disturbance.”

The parallels with the original Lavender Scare are not coincidental. They are structurally deliberate. In the 1950s, the state defined Gay and Lesbian people as security threats to justify their purging from government positions. In 2025, the state defines Trans people as threats to the coherence of public life and to ‘American values’. This is not a re-emergence of old logics. It is their continuity.

This continued thread is also alive in how pro-Palestinian students and activists, many of them racialised and Muslim, are being demonised in real time. Accusations of being “Hamas sympathisers” or ‘Hamasniks’ are deployed to cast anyone who is anti-Gazan genocide as worthy of censorship, suspension, incarceration, surveillance, intimidation, and, in some reported cases in the US specifically, actual abduction. Communities are turned into threats to quash dissent, where dissent is any critique of the interests of elites or the hoarding of power for the few. So remain silent at your peril. These systems of oppression are not separate, they are mutually reinforcing, targeting whoever dares to challenge the dominant order. That is precisely why our analysis, and our resistance, must be intersectional.

Systems, Not Individuals: Narratives Rooted in Power

When confronted with evidence of homophobia or transphobia in an organisation, a common defensive response is to pin it on a few individual bad actors – “a rogue manager,” “a biased recruiter,” “that one employee who told a homophobic joke.” But this “bad apple” analysis is a convenient fiction that obscures the real issue (Patriarchal Violence is Endemic: The Bad Apple Theory Will Not Save Us – Fearless Futures Limited) . Oppression is systemic. In the case of the Lavender Scare, it wasn’t just one or two officials with a grudge against Gay people; it was the entire U.S. government, backed by medical authorities and popular culture, perpetuating a narrative that LGBTQIA+ communities were dangerous.The same principle applies now: if LGBTQIA+ candidates are disproportionate under hired, or employees aren’t advancing, it’s usually not because one person in HR secretly hates them – it’s because inequity is baked into the ecosystem, often in invisible ways.

From that view, it becomes clear that fixing a problem like workplace transphobia isn’t about ferreting out one transphobic employee; it’s about interrogating how the structures may be furthering cissexism. For example, are dress codes forcing Trans people to conform to certain norms under threat of poor “professionalism” ratings? Are sponsorship opportunities informal and based on “chemistry” – which often means LGBTQIA+ employees, especially Trans folks, don’t get access because senior leaders choose younger versions of themselves? These are systemic issues, not solved by punishing an individual. They require deeper organisational analyses and redesign.

In sum, cissexism and heterosexism in organisations are problems that require structural solutions. It means leadership must admit that even without any ‘card-carrying homophobes’ on staff, cissexist and heterosexist outcomes may be happening.

A Call to Action for Organisational Leaders

The history of the Lavender Scare and its continued realities carry an urgent message for today’s organisational leaders: we must actively confront how these oppressive systems show up in our spaces. It is not enough to celebrate Pride Month or to have a diversity statement on your website. Structural problems demand structural action. Leaders have the responsibility – and the power – to disrupt the continuities of homophobia and transphobia in their organisations. Here are some ways forward, rooted in courage and accountability:

- Educate and Acknowledge: Make the hidden histories visible. Encourage learning among your teams about events like the Lavender Scare and other oppression histories. Why not share this article and have a team discussion?

- Audit Your Structures: Take a hard look with an equity lens at recruitment, pay, promotions, performance plans, probation processes and anywhere across your policies where Gender is at work. Where are LGBTQIA+ people falling out of the hiring process? Who thrives in your promotions process and who doesn’t – and why?

- Use data: for example, track promotion rates and performance review scores by Gender identity and Sexuality (in a voluntary, anonymous way that respects privacy and only where that data can legally safely be collected with informed consent). If LGBTQIA+ employees consistently have shorter tenures, that could be a red flag of a deeper issue.

- Conduct pay equity analyses that include LGBTQIA+ as a category ideally analyse the data intersectionality in terms of Race,Gender and other demographic categories you may collect.

- If you don’t have the data, improve your self-ID systems and climate surveys to gather it. Transparency is key – you cannot necessarily fix what you don’t measure.

- If you don’t have the data, improve your self-ID systems and climate surveys to gather it. Transparency is key – you cannot necessarily fix what you don’t measure.

- Create an Inclusive Culture: Culture change comes from both the top and the grassroots. Leaders must model inclusion – for example, by visibly supporting LGBTQIA+ employee resource groups, by using pronouns in email signatures and introductions (signaling that everyone’s identity is respected), and by having the skills to addressing remark or behaviours that further inequities both in the moment and after the fact, even if it’s uncomfortable.

- Center Intersectionality: In all these efforts, remember that LGBTQIA+ people are not a monolith. Be attentive to those who sit at multiple intersections – e.g. Queer and Trans People of Colour, or LGBTQ people made poor, or Disabled LGBTQ people – who often face compounded marginalisation. Invite their input on matters that impact them.

- Sustain and Hold Accountable: A call to action is not a one-time event. It must translate into ongoing practice. Set specific, measurable inclusion goals (for promotion gaps closing etc.), and report on progress to your organisation transparently. Tie leadership performance evaluations or incentives to inclusion and equity outcomes. When setbacks or incidents occur (they will), don’t go into a defensive mode; treat them as opportunities to learn and do better and pivot your approach, integrate vital data and/or tweak an assumption to drive alternative outcomes in the future.

Ultimately, the opposite of demonisation is proactive inclusion and equity. By confronting how the logics of demonisation continue to manifest across society and in our workplaces – and by acting decisively to dismantle them – we honor those who suffered in the past and ensure a better future. We create organisations where no one needs to hide in fear, where difference is not merely tolerated but valued, and where everyone can contribute their fullest, free from the weight of oppression. That future is possible if we are fearless enough to build it.

The Lavender Scare is not just a distant historical injustice to remember with regret – it is a call to action. It reminds us that oppressive systems can be architected and sustained by ordinary people, but they can also be challenged and disrupted by ordinary people with courage and conviction. Let’s choose the latter. Let’s commit to uprooting heteosexism, cissexism, and all oppression from our organisations by attacking them holistically: the narratives, the structures, the silences that allow them to be maintained. In doing so, we answer the harm of the past with justice in the present. We ensure that our workplaces, and our society, move closer to the ideals of equity and liberation that so many – along lines of Race, Gender, Sexuality, and more – have fought to realise.

The charge is clear: build a world where no one is demonised for who they are. The work starts in our own organisations, and it starts now. Let us be fearless in this pursuit of futures where all can thrive.