Content Warning: This article contains discussions of Gender-based violence and misogynistic ideologies.

What does it mean to come of age in a culture where to be a Boy is to be told that violence makes you a Man, and where to be a Girl is to be told that saying no might get you killed? In Netflix’s Adolescence (2025), a 13-year-old Boy is arrested for the murder of his Girl classmate. It is a harrowing fictional scenario, but it reflects a modern feature of the long-standing social system of patriarchy: the rise of incel culture, the manosphere, and rampant misogyny among some Boys and Men.

Before we get started it is essential to acknowledge that patriarchy is not the only axis upon which oppressive violence happens (racist, disablist etc). Violence can also occur in any relationship, including same Gender relationships, and people of all Genders can be perpetrators. Nevertheless, this article focuses on how patriarchy shapes the violence and control that some Men exert over Women, Girls, and marginalised Genders, with a recognition that other systems of oppression, such as racism and classism, also shape how violence manifests and who is vulnerablised.

So, why would a teenage Boy murder a Girl simply because she hurt his pride? What does this reveal about the messages young Men receive about Manhood? And how do structures like capitalism and racism reinforce this deadly patriarchal ideology?

Fearless Futures’ approach, which uses an anti-oppression, intersectional lens, insists we go beyond individual pathology into structural causes. In that spirit, this long-form article examines this specific violence as an expression of patriarchy, one intertwined with capitalism and racist ideas of Gender. We will analyse how Adolescence depicts these dynamics through its characters and plot, the role of social policing and the Police as enforcers of Gendered and Racialised control, and insights from Fearless Futures’ own webinar “Sexism and Men: What it gives, what it takes”. Finally, we consider how these forces show up in our families and workplaces, underscoring that the struggle against misogyny and oppression must be comprehensive and uncompromising.

What Patriarchy Gives (and Takes) from Men

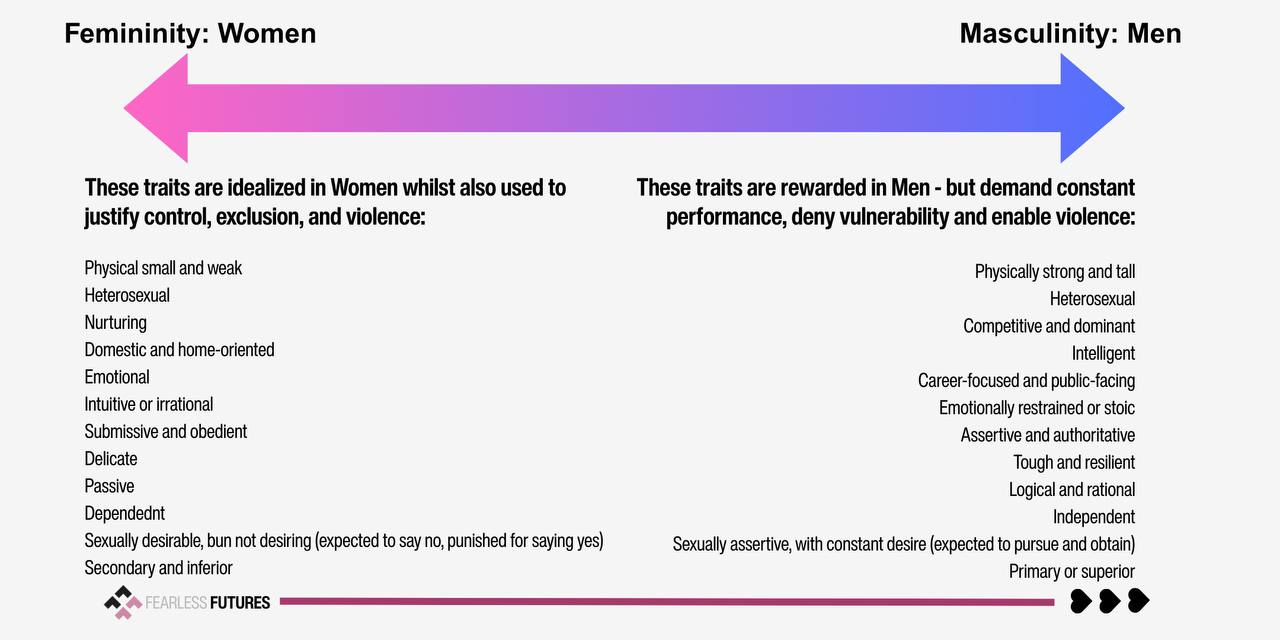

To start with, what is patriarchy? Patriarchy is a systemic pattern that positions Men as dominant over Women, Cis people over Trans and Non-Binary people, and Heterosexual people over LGB+ people. It is rooted in and upheld by a rigid Gender binary that places Cisgender Heterosexual Men at the top. The system is maintained through narratives of biological essentialism (the false idea that Men’s dominance is biologically ordained) and often through outright violence. Under patriarchy, “real Men” are deemed superior and are expected to be dominant, aggressive, and in control, while Women (and anyone feminine or Gender Non-Conforming) are deemed inferior, passive, and subservient, kept in “their place” through control and intimidation. You can see other characteristics ascribed to each Gender in this graphic:

Patriarchy is structural. This means it is not about a few bad apples but instead about historic and present laws, policies, and institutions that allocate wealth, power, resources, and status to Cis Heterosexual Men at the expense of Trans and Non-Binary people, LGB+ folks and Women, at scale. It appears in a sprawling network of examples: Section 28, the exclusion of Women from universities until very recently, the banning of Women’s football by the FA, lower wages for feminised labour, unpaid childcare, and countless other practices.

A key insight from Fearless Futures’ webinar “Sexism and Men: What it gives, what it takes” is that patriarchy is also a double-edged sword for Men. It corrodes Men’s emotional lives and relationships, which in turn drives patriarchal violence. Understanding this “bargain” helps explain why Boys like Jamie (or the real-life Boys he represents) might embrace a system that ultimately harms them, too.

Among the promises made to Men under patriarchy

- Power over others, whether in relationships, workplaces, or social settings, is framed as a marker of success.

- Access to wealth and resources is tethered to the provider role—often reinforcing the devaluation of feminised labour and unpaid care work.

- Social legitimacy, earned through performances of strength, sexual conquest, and control.

- Recognition as “real Men”, secured by reinforcing masculine norms in themselves and punishing perceived weakness in others.

In exchange, the system demands that Men relinquish:

- Emotional literacy—the capacity to name, express, and process feelings. Many Men are socialised to equate emotional vulnerability with shame, leaving anger as the only acceptable emotion.

- Authentic intimacy—relationships grounded in reciprocity and trust are replaced by hierarchies of dominance and fear of emotional exposure.

- The right to softness—especially in fatherhood, friendship, or self-expression. Nurturance, tenderness, and care are policed away as unmanly.

- Freedom from competition—Men are pitted against one another in a social ladder that offers connection only to those who win, and isolates those who don’t.

How is patriarchy enforced? Well, misogynistic violence, from domestic abuse to mass shootings, is one brutal tool by which patriarchy enforces Men’s dominance. Indeed, so-called “incels” have committed heinous acts of Gender-based mass killings rooted in the logic that Women’s autonomy is a threat to Men’s supremacy: for example, the 2014 Isla Vista massacre by Elliot Rodger (who killed six people and left a manifesto raging at Women who rejected him), and the 2021 Plymouth shooting by Jake Davison in the UK. These were not isolated “loners” or “bad apples” but men following a cultural script that tells them they are entitled to Women’s attention, their bodies, and their obedience and that any denial of that entitlement is an intolerable injustice.

The role of other oppressions and how they interact with patriarchy is worth noting. It is the case that not all Men — even Cis and Heterosexual Men — are given equal access to the rewards of patriarchy. Take, for example, Disabled Men.Patriarchy idealises masculinity as being physically strong and independent and so Disabled Men are often denied recognition as “real Men” because their bodies or needs challenge that ideal. They might be infantilised, desexualised, or excluded, even though the system still pressures them to perform masculinity in harmful ways. Or consider Muslim Men, who are often racialised and positioned as inherently dangerous and controlling. While patriarchy demands they embody masculinity, Islamophobia positions their masculinity as a unique threat, leading to hyper-surveillance, incarceration and media demonisation. Similarly, some Women are denied access to femininity and Womanhood because of how racism shapes Gender. And because Gender in the Global North is based on White Europeanness. The case of Cis Women of Colour elite athletes and the abuse they face at the hands of many sporting institutions is an expression of this racist Gendered policing. So patriarchy is not a flat system — it always works in relationship with intersecting systems like racism, disablism, Islamophobia, and more, to inform how people are advantaged and disadvantaged and to what degree.

Nevertheless, patriarchy asks Men to harden themselves into a narrow mould and, in return, offers them a slice of power. Many Men accept this bargain, especially those who benefit most (Cisgender, Heterosexual, Non-Disabled Men who fit societal ideals). Others feel the bargain fails them. They do not gain the social or sexual rewards they believe being a “Man” entitles them to (perhaps they are shy, not conventionally attractive, or economically insecure). Because patriarchy teaches Men that obtaining these rewards is their birthright, falling short is framed as a personal failure at “being a Man.” Patriarchy provides no healthy way for Men to process the resulting pain, so they turn to the manosphere for answers.

The “manosphere” describes a range of digital communities (incel forums, men’s rights activists, “red pill” spaces, and pick-up artist guides) that share blogs, podcasts, video channels, and e-commerce promoting Men’s entitlement, grievance, and hatred toward Women and marginalised Genders. This subculture is increasingly crossing from online into real-life violence.

As our webinar noted, it “promises that by following certain rules it is possible to ‘win at being a Man.’” This parallels patriarchy’s mandate to prove one’s Manhood constantly. Online “gurus” sell methods for building muscle, making money, manipulating Women into sex, or otherwise gaining status, but it always involves dominating Women and marginalised Genders and shaming other Men. The manosphere flatters many Men’s socialised sense of superiority, telling them it is not their fault; it is Women’s fault. Feminism is to blame. “Men are the real victims now,” they say, because Women refuse to be submissive anymore. This is a seductive message for Men steeped in patriarchal values yet personally unfulfilled by them.

The tragedy is that this “cure” is the original poison in another bottle. Women are not to blame; patriarchy is. Far from teaching Men to heal or grow, the manosphere traps Men in rage, fear, and isolation, insisting empathy is weakness and that respect and love are zero-sum games.

What makes the misogynistic culture across the manosphere especially alarming is how it has metastasised online and become intertwined with other oppressive ideologies. Researchers and journalists who have ventured into incel forums describe a cesspool of hate: rape jokes and rabid racism are rampant, couched in meme humour that masks the venom. In these spaces, Women are dehumanised as “holes” or “foids” (short for “femoids”), reducing them to subhuman objects. The misogyny is often accompanied by racism and homophobia, unsurprisingly, since the incel worldview idolises a retrograde, Hetero-Cis-Masculine ideal that is White by default. Any Woman who isn’t thin and conventionally attractive, as articulated by European Whiteness, may be targeted with fetishisation or racist slurs, and LGBTQ+ and Trans people are derided for defying the Gender binary. In other words, incel culture sits at the crossroads of patriarchy and White supremacist ideologies.

Another critical layer to this story is capitalism. Patriarchy and capitalism have long been intertwined systems, each propping up the other. Capitalism relies on patriarchal Gender roles (and racism) to extract free or cheap labour from Women (through unpaid caregiving, underpaid service work, etc.), just as patriarchy relies on Men’s economic power to keep Women dependent. In incel discourse, we see twisted reflections of capitalist ideology: a transactional view of relationships (where Men see sex as a ‘birthright’ ), a competition for status among Men, and a fixation on looks and wealth as markers of worth. Capitalism generates narratives that ‘if you work hard enough, you can make it’ and that anyone can ‘pull themselves up by the bootstraps’. In reality, it’s an economic regime designed explicitly for a tiny few to extract inordinate wealth from the majority. Capitalism and Patriarchy simultaneously position Men as the necessary and singular legitimate ‘Breadwinners’ and those who get paid for their labour. Both systems tell us that men uniquely exist to be the providers and breadwinners for their families, with Women as dependent, unpaid, and homemakers. Under Neoliberal capitalism, as economies have transformed, many Men find themselves unable to deliver against this unfair role criteria and set of expectations. Systems of oppression consistently invisiblise their mechanics and instead present individuals as failures. Incel culture and the manosphere take advantage of this valid rage at the systemic realities that produce these outcomes and instead stoke the flames and misdirect them towards Women.

We could liken the misdirection of incel culture and the communities of the manosphere to people who rightly see their communities denied the resources needed to function and who are struggling to make ends meet who then determine that refugees, migrants and People of Colour are the problem (rather than extractive employers and unfair government policy).

These are both classic scapegoating manoeuvres where systemic oppression has us pointing the finger at groups who are structurally disenfranchised. Feeling ‘emasculated’ by a world of unattainable success and endless hustle, these Men are told that the real reason they’re unhappy is that Women have become too “empowered” and won’t give them the sex and validation they deserve. In this way, incel culture repackages economic justice into a narrative of patriarchal grievance, the cry that Male privilege is a birthright being unjustly denied.

The allure of this narrative should not be underestimated. Jack Thorne, the writer of Adolescence, candidly admitted that when he researched incel forums, he “quickly grasp[ed] the attraction” of the manosphere for a struggling teen Boy. The idea that “80% of Women are attracted to 20% of Men,” a common incel trope, might have made his own adolescent self “sit up and, frankly, nod” in agreement. If a young Man comes to believe this (essentially that a minority of “alpha” Men get all the Girls, leaving most Boys unfairly deprived), it’s a short leap to “What do you do to upset that equation?” and to rationalising manipulation or harm to “reset a [supposedly] female-dominated world that works against you”. In other words, once a youth accepts the lie that Women have all the power in the dating world and are deliberately denying him his due, violence starts to seem like justified retribution. This is patriarchal logic inverted: rather than Men as a group being structurally advantaged over Women, incel ideology paints Women as the “oppressors” (for not sleeping with them) and Men as the ‘hapless victims’ who must “fight back.” It’s a perverse reversal that appeals to those who cannot face the painful truth that the real enemy is an unjust system, not the Girls who won’t go out with them.

Masculinity and Misogyny

Jack Thorne’s Adolescence brings the structures of patriarchy into sharp and intimate focus. The four-part drama follows Jamie Miller, a 13-year-old from Northern England, after he is arrested for stabbing his classmate Katie to death. Early in the story, viewers learn through undeniable evidence that Jamie did kill Katie. The question the series asks repeatedly is not whether, but why. There is no singular traumatic incident to point to, no clearly abusive adult, and no cinematic flashback to offer an easy answer. Instead, the show presents the cumulative environment that shaped Jamie’s world: toxic digital content, warped constructions of masculinity, and a peer culture where misogyny is ambient, unexamined, and normalised.

Masculinity and misogyny appear as mutually reinforcing structures in Jamie’s life. Katie and other classmates had publicly ridiculed him online after he awkwardly asked Katie out. His timing was opportunistic, taking place after a private topless photo of Katie had been leaked in school. When Katie rejected him and called him an “incel,” other students amplified the moment with mocking emojis. The term “incel” was used to humiliate him, to position him as socially inferior. While it functioned as a joke among peers, it landed as a deep wound. The story suggests that Jamie’s pride and emotional world were shaped by patriarchal norms that equated rejection with emasculation. His lethal response emerged from the belief that dominating her, in this case in the most extreme way, could restore what he had lost.

This is how patriarchy trains some Boys to perceive refusal. Jamie believed that Katie owed him her affection or, at minimum, her deference. When she withheld it and humiliated him, he responded with devastating violence. Under patriarchy, this dynamic is familiar. Girls and Women are punished for saying no, for withdrawing attention, or for asserting boundaries. Incel forums celebrate such punishment. These spaces glorify Men who retaliate against rejection, and frame this retaliation as a correction. Violence becomes a strategy to re-establish a fragile dominance. When the Gender binary is disrupted, violence is deployed to restore its terms. The act of harm is not an outlier. It is a method of reasserting the conditions through which power is meant to flow.

The series also shows how early this dynamic takes root. Jamie’s interactions with adults are steeped in posturing. In one episode, Briony, a child psychologist played by Erin Doherty, attempts to evaluate him. Their conversation reveals how much Jamie has already absorbed from online misogynist spaces. He mirrors her speech, mocks her mannerisms, and delivers backhanded compliments. These are tactics drawn directly from the manosphere. Viewers witness a Boy rehearsing dominance, trying to unsettle and unseat a Woman’s authority with strategies learned online. He believes power is something to perform, not something to question.

Briony refuses to be manipulated. She remains calm and direct, asking questions that chip away at Jamie’s surface. The scene is quietly charged. A Boy, barely adolescent, enacts Gendered control patterns that many grown Men have lived for decades. A Woman sits across from him refusing to yield. Her strategy is not punishment or shaming. She holds space while challenging the logic he has inherited. By the end of their exchange, Jamie is visibly shaken. Something has shifted. The systems that taught him how to behave have not equipped him to respond to care.

There is another layer to consider in how Adolescence tells its story. The series is explicitly focused on the conditions that produce Male violence. However, its narrative structure ends up marginalising the Girl whose life was taken. Katie is present for much of the story, but by the final episode, she has almost disappeared. Her name is barely spoken. The only other Girl, Jade, also exits the story without closure. This narrative shift reflects a broader pattern. In both fiction and public life, Girls and Women harmed by Gendered violence are often made secondary. The story becomes about the Man, the Boy, the perpetrator, or the environment that shaped him. The victim’s name fades. The conditions of her death are studied more closely than the reality of her life.

This structural erasure has consequences. It communicates that the one harmed can be remembered only in relation to the one who harmed them. Even in death, Katie must be understood through Jamie. She is not offered complexity, interiority, or legacy beyond the moment of violence. She is admired for her good grades and her kindness, but only so she can be mourned with dignity. The message is that Girls must be exceptional to even be grieved properly. The attention shifts quickly away from the life lost and toward the community’s reckoning with the Boy who caused that loss.

These narrative choices mirror cultural practices. Time and again, Men’s violence is interpreted through the language of provocation, rejection, or tragedy. Girls and Women harmed are mourned quietly and briefly, unless they fit an idealised image of perfection. Many are simply forgotten. Even within stories meant to expose misogyny, the risk remains that the structural violence will overshadow the person at its center.

Adolescence succeeds in exposing how patriarchal norms shape young Men. But it also reminds us that telling the story of harm requires care, especially when that harm is Gendered. Misogyny does not only wound. It erases.

Policing, Patriarchy, and Racialised Control

Notably, Adolescence does not portray Jamie as a monstrous aberration born of parental failure. His father, Eddie, is a loving Working Class dad (played by Stephen Graham, who also co-created the show). Yet in a story that Jamie and his father tell independently of each other, Eddie carried a deep shame, that Jamie knew of, over Jamie’s failure to perform traditional masculinity. Both Jamie and Eddie share that Jamie’s lack of interest or skill in football that he was pushed into, was laughed at by other parents with Eddie’s uncomfortable silence speaking volumes for Jamie who noticed it. Insisting that Jamie participate in football was a method of policing his son’s Gender expression in order for Jamie to fit in with “the lads”. Jamie’s lack of skill or interest or both, leads to inadequate performance and sniggering from fellow parents – a response designed to further humiliate Jamie and punish him for not delivering on an ideal masculinity. The sniggering to humiliate is a policing mechanism.

Acting on these concerns about Jamie’s inability to live up to sporting prowess that the binary demands, even as Eddie seems to see that Jamie has talent and interest in drawing, Eddie even enrolls Jamie in a boxing class, explicit in his hopes that this would “toughen him up” – another policing manoeuvre. Why is drawing not pounced on as something that Eddie should encourage in Jamie? We must conclude that drawing is deemed a feminine hobby, one that falls outside the narrow band of traits patriarchy values in Boys. It doesn’t require physical strength, it’s not done in public, it requires delicacy. Jamie receives the message that what he enjoys and excels in has little worth, simply because it is coded as feminine. This both devalues him and also contributes to Jamie’s devaluation of Girls and Women by underlining through its prohibition that anything associated with them is inherently inferior and to be ridiculed.

In Eddie’s mind, paradoxically, boxing is a practical way to protect his son from the violence he may endure from others if he does not fulfil the demands of the Gender binary. Yet this attempt to police Jamie out of his natural demeanour and into toughness is itself a form of invisible patriarchal violence. The societal policing confirms that Jamie’s natural demeanor is inadequate, that he must learn to inflict and withstand pain to be a “real man.” While Eddie intends to help, the effect is to compound the problem: instead of addressing Jamie’s emotional needs or celebrating his unique strengths, this well-meant harshness pushes him further into shame, where violence again becomes the logical end point to restore his ‘valour’ and ‘respect’.

This deeply sad story in the show reveals so much about the role of parents in furthering patriarchy unwittingly. Eddie fears that Jamie’s gentle, non-aggressive nature reflects poorly on him as a Dad in a culture that equates a Boy’s worth – and survival – with toughness, violence and athletic prowess. He is ashamed of his son. Jamie’s shame is born from the shame he sees that his Dad feels of himself and has in him. And we know that Men enacting violence is how shame is corrected under patriarchy.

Alongside familial and social policing, one of the most interesting aspects of Adolescence is its portrayal of the Police, and what it implies about law enforcement’s role in upholding social order. In the real world, policing has long been an enforcer of patriarchal and Racial hierarchies. Police forces originated in many places as instruments to protect the property and wealth of elites. When considering the alleged nobility of the police in the UK, we might wish to consider how the first Police force was established at the London docks to prevent theft from the boats. The total hypocrisy of the Police’s social function here is of course underscored by the fact that the boats’ very product was the result of the ultimate theft: kidnapped African people, enslaved into coerced labour. That the Police are agents of any so-called ‘justice’ is also fundamentally undermined by their existence and very purpose as enforcers of the British empire from Ireland to India; their deployment against those protesting for fairness and equality from Peterloo to Palestine; in anti-apartheid actions, their uses in the early English colonies in America as ‘slave patrols’ and their presence today in modern militarised policing and surveillance of marginalised communities. Police are the enforcers between the boundary of human and un-human; the lives we care for, and the lives we don’t. Police therefore have a very specific role under systems oppressions: as enforcers of the already existing unequal status quo.

We must ask ourselves, if the Police really are in service of justice, why is it that:

- The Police do not prevent employers exploiting their staff through inadequate wages and poor working conditions – but they do arrest shoplifters who aren’t afford food for their families.

- The Police do not arrest Big Oil executives for their role in climate catastrophe – but they do arrest Just Stop Oil activists involved in civil disobedience to raise awareness of climate catastrophe.

Whose justice?

Moreover, Police forces themselves often embody the very injustices they claim to mitigate. A damning official report in the UK – the 2023 Casey Review – found that London’s Metropolitan Police was institutionally misogynistic, racist and homophobic, plagued by a culture of bullying and bias within its ranks. While many may reach for the ‘bad apples’ explanation, history tells us as detailed above that this is exactly as it’s meant to be.

Studies also suggest anywhere between 4.8–40% of police officer families (in the US) experience domestic violence, with some sources estimating officers are four times more likely to engage in domestic violence than the general population. There is no reason to expect different dynamics in other countries. Whether it’s that engaging in power with impunity attracts those who crave this, or that being in the Police confirms impunity that makes violence more likely – is neither here nor there. An entity with a specific role to deliver under systems of oppression – which is on the side of the oppressive status quo – cannot be engaged in or relied upon to enact anything just.

Crucially, the police in Adolescence are shown not just failing to prevent violence, but at times actively perpetrating it. One of the most disturbing moments in Adolescence drives this point home: the strip search of Jamie at the police station. At just 13 years old, Jamie is forced to undergo an invasive, degrading search by two Men officers, presented as standard procedure, yet unmistakably a form of state-sanctioned sexual violation. It’s a harrowing scene – made more so when we see incontrovertible evidence minutes later that confirm his guilt. Why was this strip search necessary? It simply wasn’t. But it was desirable by the institution, which requires consistent assertion of its domination. It underlines how the machinery of law enforcement itself violates and traumatises individuals. The entire ‘criminal justice’ apparatus has non-consensual bodily violation embedded throughout it. Strip searches of incarcerated people are routine in prisons. Sexual violence is routine in prisons. Trans people’s bodily self determination is erased through physical misgendering in the prison system.

Bodily autonomy is either a principle for each and every one of us at all times, or it isn’t. Further, if bodily sanctity is a principle for your kid, it’s a principle for all kids, including Jamie, including any ‘suspects’. The strip search sequence is an illustration that the state’s “justice” process creates new violence, rather than providing remedy.

Any possibility of ‘justice’ in this show ultimately feels inadequate when the underlying system that produced the violence remains entirely intact. We see it for what it is: a reactive, administrative force. The Police, as well as the school, actually, do nothing to prevent harm. Despite popular myths about “keeping the peace,” the Police typically enter the picture only after violence has occurred (if they aren’t actually delivering it, as in the cases of Rashan Charles, Chris Kaba, Mark Duggan and others, where we must also note that Men of Colour are twice as likely to die from lethal force as White Men, in the UK). They file reports, make arrests, and manage the aftermath, but they cannot and do not stop misogynistic harm before it happens. And crucially, the Police offer no possibilities for repair between perpetrator and victim, no meaningful accountability, and certainly do not honour what survivors may need to heal. The system does not provide services or care for the survivor. It simply offers the possibility of caging someone, who, when released, will enter a world with exactly the same conditions that drove the behaviour beforehand. “Criminal justice” – and in many ways our school system too – is only concerned with disposing of people, pushing them out of sight and into cages.

Change Starts at Home: Parenting, Caregiving, and the Gender Binary

In the final episode, Jamie’s parents are left grasping. Manda, his mother, insists on taking some responsibility and urges Eddie to reflect on his own role. Eddie begins to question how Gender shaped their home, though he does not yet have the language to name what he is seeing. While the government’s public response to Adolescence has focused on surface-level reforms—more Men in nurseries, more Men teachers in schools, mandatory “anti-misogyny” workshops—one group remains largely absent from the conversation: parents, guardians, and caregivers.

Children learn what Gender means from the very beginning. Studies show that children have a sense of their own Gender identity by the age of four. What they see, hear, and feel before that age shapes what they come to believe is possible for themselves and others. Adolescence shows that even in a household with care and commitment, the Gender binary was constantly reinforced. It was reinforced through sports, through shame, through missed opportunities to affirm softness and creativity. The lesson was clear: to be a Boy is to fit the mould, and to fail to fit is to be punished.

The solution is not to train Boys to better manage their emotions. It is to dismantle the idea that Boys must become Men in any specific form. The Gender binary must be made unstable. It must be rendered flexible, fluid, and ultimately irrelevant to how children are seen, supported, and celebrated.

This begins with each of us. We must interrogate our own investments in the binary. Why is it so important to learn the “Gender” of a baby before it is born? What do we imagine that tells us? Are we already mapping out their personality, their preferences, their future, based on that one detail? When we do that, we are limiting their humanity before they even arrive.

There are practical steps that caregivers and educators can take to destabilise Gender from the very beginning:

- Avoid using Gendered language to label them. “You’re a good ‘boy’” or “you’re a good ‘girl’”. Can there be space for them to just be ‘a child’, without Gendered constraints we reinforce, for as long as possible? If they believe you’re very committed to them being a ‘Girl’ or a ‘Boy’, will they be able to tell you if they aren’t?

- Renounce familiar Gendered phrases from your repertoire. Boys don’t need to be ‘a big Boy’ and they can most certainly cry. Specifically with Boys, encouraging emotions of sadness, grief, disappointment and frustration and welcoming them all even when you’re time pressed and stressed is vital. When these emotions get quashed, for fear it makes them weak, Boys learn that only rage is permissible. We cannot have that for them, or for the rest of us.

- Renounce phrases that police Girls into ‘obedient femininity’. Encourage them to climb, and crawl and roll and tumble and take up physical space. It is not a genetic predisposition that they sit quietly and still. They do not need to be managed and controlled. Patriarchy does enough of that already.

- Encourage bodily autonomy for all kids. Welcome their ‘nos’ even if it’s socially awkward with their relatives. No person, or child, owes someone a hug or a kiss. There can be other ways to express affection. Perhaps a fist bump, high five, wave, or even just verbally. This is a vital bodily boundary for all children: to both express and to respect ‘nos’.

- Refer to people – other kids and adults – as they/them until you’ve asked their pronouns and who they are. “Look at that Man riding his bike!” your child may scream, and you can respond “Oh yes, I see that person on their bike!”.

- When teaching body parts, let them know that Boys can have vaginas and Girls can have penises. Because this is true. And scientific fact.

- Mix up people’s pronouns when reading stories to your kids. Yes ‘he’ might be called ‘Harold’ and have short hair. But Harold could also be a she too.

- Ensure they know that not everyone is a ‘he’ or a ‘she’ and some folks don’t feel quite like either and therefore are ‘they’.

- Over indexing for the clothing colour of the “opposite Gender”. Particularly in a world where anything coded as feminine is ridiculed and devalued, putting Boys in ‘pink’ and other feminine coded clothing is important (even if you don’t like the colour). It signals that what’s associated with Girls is valued, it destabilises others people’s perceptions of Gender, and teaches them that they can be fully expressed.

- Physical appearance is not an indicator of one’s Gender. We don’t know until we are told. Hold this line and practice it. It isn’t the ‘nice lady at the check out’ – it’s ‘the nice person’. This might feel pedantic. But Gendered scripts lay the foundations and do the work of patriarchy.

- Some people have “two mummies” some have “two daddies” some have only one parent, others have two or more parents. Practice introducing this range into your conversations with your children. Find stories to read to further articulate this.

- No sport or job belongs to a Gender. Men can and should engage in the full range of house work. Consistently. Insistently. Without fanfare. And Women can do plumbing.

All of these practices help disrupt the rigid scripts that patriarchy depends on. And they matter deeply, because schools are unlikely to challenge these scripts at scale. If home is where Gender is first enforced, it must also be where liberation begins. We cannot wait for curriculum reform. We must plant the seeds of undoing now.

There is more to be said about how schools, workplaces, and digital cultures continue to shape these dynamics. That is for another day. But today, we name the design. We name the cost. And we return to where change begins: at the root, in the home, with how we name our children, how we touch their hearts, and how we allow them to become.

From Adolescence to the Workplace: Confronting Entitlement and Grievance

In a 2025 global survey of 24,000 people across 30 countries, a shocking 57% of Gen Z Males agreed that “society has gone so far in promoting Women’s equality that Men are being discriminated against”. In other words, a majority of young Men worldwide see Gender equity not as a win-win, but as a zero-sum game they are now losing. This is exactly the kind of Gender grievance politics that incubates in the manosphere and then seeps into real life.

We hear it in workplaces when Men colleagues grumble that a Woman only got a promotion because of “diversity hiring,” ignoring her qualifications. We hear it when they dismiss sexual harassment training as “political correctness.” This inversion of reality is a hallmark of reactionary politics. It reframes the reduction of structural advantages as persecution. If you have been accustomed to patriarchal privilege, to being the default leader, the default voice in the room, then equitable change can feel like a personal attack. As the saying goes, “When you’re used to privilege, equality feels like oppression.”

The workplace is a key site of power distribution. Add a Man influenced by incel ideology (perhaps he spends his evenings on Reddit reading about how feminism is “ruining everything”), and that environment becomes hostile to Women and LGBTQIA+ colleagues. Some Men sabotage or harass coworkers, or form whisper networks to resist supposedly “politically correct” policies. Diversity, equity and inclusion programmes have limited impact if they are just box-checking. We need a systemic approach that clarifies oppression is not about finger pointing at individuals, but about systems producing unfair outcomes.

In Adolescence, the tragedy was that adults did not understand or see what was festering until it was too late. In our companies and offices, we mostly have the benefit of knowledge. We know there is an issue when the likes of Andrew Tate have millions of followers who are workers, students, and neighbours among us. We cannot afford to ignore these warning signs. Confronting incel ideology and misogyny in the workplace is not only about preventing extreme violence. Shootings and domestic violence spilling into work are real concerns. It’s also that Men, as humans, have much to gain from a more equitable workplace. This includes freedom to be themselves without macho posturing, deeper relationships with their kids, richer professional relationships based on respect and kindness, and a fairer environment where they too are valued for who they are rather than antiquated Gender expectations.

As we reflect on Adolescence and the real-world rise of incel culture, the overarching lesson is that oppression is a system. It ultimately harms everyone, though unequally. The incel phenomenon is an extreme outgrowth of the same patriarchy whose roots run through our institutions and norms. Challenging it requires structural analysis at every turn. We cannot simply dismiss incels as “deranged loners” and carry on. We must examine how our society, through media, health institutions, the economy, and socialisation, produced their worldview. Likewise, we cannot treat workplace sexism or the ‘DEI backlash’ as isolated gripes; they are part of that broader structural push-pull as the old hierarchies are contested.

Patriarchal violence, whether through online harassment, domestic abuse, or inequitable workplace promotions process is not a series of disconnected incidents. It is a continuum upheld by intersecting systems of asymmetric power: patriarchy, racism, classism, disablism and more. The police officer, the father, the teenage Boy, the CEO, the lover – as are we all – are operating within these systems. But if those of us committed to equity do the hard work, they can operate differently. We can raise Boys with emotional intelligence and respect for boundaries. We can build economic systems that do not equate Manhood with ruthless competition. We can cultivate bodily autonomy in Girls and us all.

At the end of Adolescence, we see grief: grief for a Girl who lost her life, for a Boy who lost his way, and for the families and communities shattered. We are also left with a mandate to change the story. Adolescence shows compassion for Jamie without excusing his actions, keeps Katie’s presence felt for a time, and emphasises how many Girls and Women suffer or die while we fail to teach Boys about masculinity in healthier ways. It reminds us that Boys navigate an impossible world with little emotional support. Katie’s death is the height of tragedy, but Jamie’s lost innocence also stings. We must rethink how we socialise Boys and Men if we hope to end this cycle of violence.

Undoing patriarchal oppression is challenging but critical, as it affects the lives of Women, Girls, marginalised Genders, and Men and Boys themselves. In the anti-oppression philosophy that guides Fearless Futures, removing these oppressive structures liberates us all to become more fully human, which is more than worth the effort.

Sources:

- Fearless Futures, Sexism and Men: What it gives, what it takes

- Lucy Mangan, “Adolescence review – the closest thing to TV perfection in decades,” The Guardian (13 Mar 2025) (Adolescence review – the closest thing to TV perfection in decades | Television & radio | The Guardian) (Adolescence review – the closest thing to TV perfection in decades | Television & radio | The Guardian).

- Jack Thorne, “The younger me would have sat up and nodded: Adolescence writer on the insidious appeal of incel culture,” The Guardian (18 Mar 2025) (‘The younger me would have sat up and nodded’: Adolescence writer Jack Thorne on the insidious appeal of incel culture | Television | The Guardian) (‘The younger me would have sat up and nodded’: Adolescence writer Jack Thorne on the insidious appeal of incel culture | Television | The Guardian).

- Olivia B. Waxman, “How Netflix’s Gripping Adolescence Takes on the Dark World of Incels,” TIME (25 Mar 2025) (Breaking Down Netflix’s Crime Drama Adolescence | TIME) (Breaking Down Netflix’s Crime Drama Adolescence | TIME).

- Rachel Rasker, “The truth behind Adolescence, the new Netflix series exploring incels and Andrew-Tate-style misogyny,” ABC News (19 Mar 2025) (The truth behind Adolescence, the new Netflix series exploring incels and Andrew-Tate-style misogyny – ABC News) (The truth behind Adolescence, the new Netflix series exploring incels and Andrew-Tate-style misogyny – ABC News).

- Natalie Cornish, “‘Adolescence’ Is a Terrifying Cautionary Tale on the Dangers of Incel Culture,” Harper’s Bazaar (20 Mar 2025) (“Adolescence” Is a Terrifying Cautionary Tale on the Dangers of Incel Culture) (“Adolescence” Is a Terrifying Cautionary Tale on the Dangers of Incel Culture) (“Adolescence” Is a Terrifying Cautionary Tale on the Dangers of Incel Culture).

Jamie Grierson, “Met found to be institutionally racist, misogynistic and homophobic – Casey report,” The Guardian (21 Mar 2023) (Met has ‘nowhere to hide’ after damning Casey report, say campaigners | Metropolitan police | The Guardian).